My impression is that 80 to 90 percent of the poems that

came to us for the Hindi version of Manushi, and at least half of

those for English Manushi, revolved around the mythological Sita,

or the writer as a contemporary Sita, with a focus on her steadfast

resolve, her suffering, or her rebellion. Sita loomed large in the

lives of these women, whether they were asserting their moral strength

or rebelling against what they had come to see as the unreasonable

demands of society or family. Either way Sita was the point of reference

— an ideal they emulated or rejected. I was very puzzled by

this obsession, and even began to get impatient with the harangues

of our modern day Sitas.

And then came the biggest surprise

of all. The first poem I ever wrote was in Hindi, and was entitled,

Agnipariksha. I give some extracts in a rough translation:

I too have given agnipariksha,

Not one — but many

Everyday, a new one.

However, this agnipariksha

Is not to prove myself worthy of this

or that Ram

But to make myself

Worthy of freedom.

Every day your envious, dirty

looks

Reduced me to ashes

And everyday, like a Phoenix, I

arose again

Out of my own ashes ........

Who is Ram to reject me?

I have rejected that entire society

Which has converted

Homes into prisons.

Not just me, even my former

colleague, Ruth Vanita, who is from a Christian family, wrote

many a poem around the Sita theme. Her recent collection of

poems has several poems that revolve around the Sita symbol.

It took a long time, but eventually I became conscious that

this obsession with Sita needs to be understood more sensitively

than I was hitherto prepared for. Therefore, I began to ask

this question fairly regularly of various men and women I

met over the years: who do they hold up as an example of the

ideal man and ideal woman? Young girls tend to name public

figures like Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, Indira Gandhi, and

Mother Teresa as their ideals. But those already

married or on the threshold

of marriage very frequently |

|

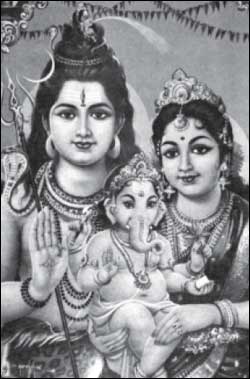

| A modern calendar representation of Ram and Sita |

|

mention Sita as their ideal (barring the few who are avowedly feminist).

At this point of their lives, the distinction between an ideal woman

and an ideal wife seem to often get blurred in the minds of women.

That includes not just women of my mother or grandmother’s generations

but even young collegegoing girls — not just those in small

towns and villages, but also those in metropolitan cities like Delhi.

Even among my students in the Delhi University college

where I teach, Sita invariably crops up as their notion of an ideal

woman. She is frequently the first choice if you ask someone to

name a symbol of an ideal wife. When I ask women why they find this

ideal still relevant, the most common response is that the example

Sita sets will always remain relevant, even though they may themselves

not be able to completely live up to it. This failure they attribute

to their living in kalyug. They feel that in today’s debased

world it is difficult to measure up to such high standards. However,

most women add that they do try to live up to the Sita ideal to

the best of their ability, while making some adjustments keeping

present day circumstances in view.

Importance of Being Sita

Since I don’t have the space

to quote extensively from the large number and variety of

interviews I have done on the subject, I merely give the gist

of what emerged out of these interviews.

It is a common sentiment among Indian women (and men) that

the ideals set in bygone ages are still valid and worth emulating,

though they admit few people manage to do so in today’s

world. This attitude contrasts sharply with the popular western

view that assumes that people in by-gone ages were less knowledgeable,

were far less aware and conscious of their rights and dignity,

had fewer options, and therefore were less evolved as human

beings. This linear view of human society makes the past something

to be studied and kept in museums but is not expected to encroach

upon the supposedly superior wisdom of the present generation.

In India, on the other hand, Ram and Sita are not seen as

remote figures out of a distant past to be dismissed lightly

just because we are living in a different age and have evolved

different lifestyles. They are living role models seen as

having set standards so superior that they are hard to emulate

for those living in our more “corrupt” age, the

kalyug.

My interviews indicate that Indian women are not endorsing

female slavery when they mention Sita as their ideal. Sita

is not perceived as being a mindless creature who meekly suffers

maltreatment at the hands of her husband without complaining.

Nor does accepting Sita as an ideal mean endorsing a husband’s

right to behave unreasonably and a wife’s duty to bear

insults graciously. She is seen as a person whose sense of

dharma is superior to and more awe inspiring than that of

Ram — someone who puts even maryada purushottam Ram

— the most perfect of men — to shame. She is the

darling of Kaushalya, her mother-inlaw, who constantly mourns

Sita’s absence from Ayodhya. She worries about her more

than she does for her son Ram. As the bahu of Avadh, she is

everyone’s dream of an ideal, loving daughter-in-law.

To the people of Mithila, she is far more divine and worthy

of reverence than Ram. |

|

| The abandoned Sita with her newborns in Balmiki’s

ashram |

| |

|

| Ram’s rejection of Sita is

almost universally condemned while her rejection of

him is held up as an example of supreme dignity. |

|

Her father-in-law, Dashrath, and her three brother-in-laws dote

on her. Ram has at least some enemies like Bali who feel wronged

and cheated by him. Ram can become angry and act the role of an

avenger. Sita is love and forgiveness incarnate and has no ill feelings

even for those who torture her in Ravan’s captivity.

In many folk songs, even Lakshman, the forever obedient and devoted

brother of Ram, takes Sita’s side against his own brother

when Ram decides to banish Sita. In one particular folk song, he

argues with Ram: “How can I abandon a bhabhi such as Sita

who is like food for the hungry and clothes for the naked? She is

like a cool drink of water for the thirsty. She is now in full term

of pregnancy. How can I cast her away at your command?” (Singh,

1986)2 He is in such pain at having to obey and carry

out such an unjust command of his king and elder brother that he

does not dare disclose the true intent of their trip to the forest.

Squirming with shame, he leaves her there on a false pretense

She is a woman who even the gods revere, a woman who refuses to

accept her husband’s tyranny even while she remains steadfast

in her love for him and loyalty to him to the very end. People commonly

perceive Sita’s steadfastness as a sign of emotional strength

and not slavery, because she refuses to forsake her dharma even

though Ram forsook his dharma as a husband. Most women (and even

men) I have spoken to on the subject refer to her as a “flawless”

person, overlooking even those episodes where she acts unreasonably

(e.g., her humiliating Lakshman with crude allegations about his

intentions towards her), whereas Ram is seen as possessing a major

flaw in his otherwise respect worthy character because of the way

he behaved towards his wife and children.

When gods go wrong

|

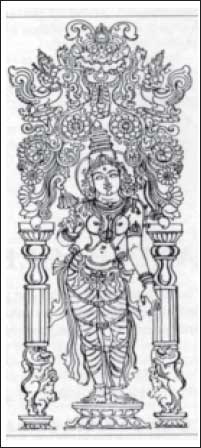

| Sita: Purna - trayisvara temple, Tripunnitura |

|

Hindus talk of Ram and Sita, Shiv

and Parvati and sundry other gods in very human ways and feel

no hesitation in passing moral judgements on them. Very few

Hindu men or women justify those actions of these deities

which they consider wrong or immoral by contemporaneously

upheld standards of morality. In other words, gods and goddesses

are expected to live up to the expectations of fair play demanded

by their present day worshippers. Their praiseworthy actions

are neatly sifted from those where the gods fail to uphold

dharmic conduct. Such criticism and condemnation is not seen

as a sign of being irreligious or irreverent but as an acknowledgement

that even gods are not perfect or infallible. This provides

a far greater sense of freedom and volition to individuals

within the Hindu faith than in religions where god’s

commandments are to be unconditionally obeyed and the god

is upheld as a symbol of infallibility.

Sita’s offer of agnipariksha and her coming out of

it unscathed is by and large seen not as an act of supine

surrender to the whims of an unreasonable husband but as an

act of defiance that challenges her husband’s aspersions,

as a means of showing him to be so flawed in his judgement

that the gods have to come and pull up Ram for his foolishness.

Unlike Draupadi, she does not call upon them for help. Their

help comes unsolicited. She emerges as a woman that even agni

(fire god) —who has the power to destroy everything

he touches — dare not touch or harm. Thus, in popular

perception Sita’s agni pariksha is not put in the same

category as the mandatory virginity test Diana had to go through

in order to prove herself a suitable bride for Prince Charles,

but rather as an act of supreme defiance on her part. It only

underscores the point that Ram is emotionally unreliable and

can be unjust in his dealings with Sita, that he behaved like

a petty minded, stupidly mistrustful, jealous husband and

showed himself to be a slave to social opinion. Most women

and men I interviewed felt he had no right to reject and humiliate

her or to demand an agnipariksha.

Rejection of Ram

The refusal of Sita to go through a second agnipariksha —

which Ram demands in addition to the first one that she had

offered in defiance — has left a far deeper impact on

the popular imagination. It is interpreted not as an act of

self annihilation but as a momentous but dignified rejection

of Ram as a husband. It is noteworthy that Sita is considered

the foremost of the mahasatis even though she rejected Ram’s

tyrannical demand of that final fire ordeal resolutely and

refused to come back and live with him. It is

he who is left grieving for

her and is humbled and |

rejected by his own sons. Ram may not have rejected her as a wife

but only as a queen in deference to social opinion, but Sita rejects

him as a husband. In Kalidasa’s Raghuvansha, after her banishment

by Ram, Sita does not address Ram as Aryaputra (a term for husband

that literally translates as son of my fatherin- law) but refers to

him as ‘King’ instead. For instance, when Lakshman comes

to her with Ram’s message, she conveys her rejection of him

as her husband in the following words: “Tell the king on my

behalf that even after finding me pure after the fire ordeal he had

in your presence, now you have chosen to leave me because of public

slander. Do you think it is befitting the noble family in which you

were born?” (Kalidasa)3

His rejection

of Sita is almost universally condemned while her rejection of him

is held up as an example of supreme dignity. By that act she emerges

triumphant and supreme; she leaves a permanent stigma on Ram’s

name. I have never heard even one person, man or woman, suggest

that Sita should have gone through the second fire ordeal quietly

and obediently and accepted life with her husband once again, though

I often hear people say that Ram had no business to reject her in

the first place.

Despite the Divorce

Ram may have forsaken Sita, but the power of popular sentiment

has kept them united. Her name precedes Ram’s in the

popular greeting in North India: Jai Siya Ram, as also in

several bhajans and chants. He is seen as incomplete without

her. He stands alone only in the BJP’s propagandaand

posters. Otherwise he is never worshipped without his spouse.

There is no Ram mandir without Sita by his side. However,

there is at least one Sita mandir that I personally know of

where Sita presides without Ram. I was introduced to it by

the workers of Shetkari Sangathana. This is in Raveri village

of Yavatmal district in Maharashtra. The people of the village

and surrounding areas tell a moving story associated with

the Sita mandir in the area, about how that temple came to

be. When Sita was banished by Ram, she roamed from village

to village as a homeless destitute. When she came to this

particular village, she was in an advanced stage of pregnancy.

She begged for food but the villagers, for some reason, did

not oblige. She cursed the village, vowing that no anaj (grain)

would ever grow in their fields. The villagers say that until

the advent of hybrid wheat, for centuries, no wheat grew in

their village, though plenty grew in neighbouring villages.

The villagers all believe in Sita mai’s curse. Her two

sons were both said to have been born on the outskirts of

the village, where a temple was built commemorating Sita mata’s

years of banishment.

Apologia for Ram

The injustice done to Sita seems to weigh very heavily on

the collective conscience of men in India. Those few who try

to find justifications for Ram’s cruel behaviour towards

Sita take pains to explain it in one of the following ways:

• Ram did it not because he personally doubted Sita

but because of the demands of his dharma as a king; he knew

she was innocent but he had to show his praja (subject) that

unlike his father, he was not a slave to a woman, that as

a just raja he was willing to make any amount of personal

sacrifices for them.

• It was an act of sacrifice for him as well. He suffered

no less, and lived an ascetic life thereafter;

• He banished only the shadow of Sita. He kept the real

Sita by his side all the time.

Shastri Pandurang V. Athavale’s interpretation typifies

the far-fetched apologia offered by those who wish to exonerate

Ram. They even drag in the modern day holy cow of nationalism

in an attempt to explain away his conduct: “What we

have to remember is that it was not Ram who abandoned Sita;

in reality it was the king who abandoned the queen, in the

performance of his duty. He had to choose between a family

or a nation. Ram sacrificed his personal happiness for the

national interests and Sita extended her full co-operation

to Ram. To perform his duty as a king, Ram had sacrificed

his queen, not his wife.... At the time of performing Ashvamedha

Yagna, many requested Ram to marry another woman [which could

be done according to the command of holy scriptures].Ram firmly

replied to them: ‘In the heart of Ram there is a place

for only one woman and that one is Sita.’”

|

The ruins of Sita mandir, Yeotmal

Distt, Maharashtra |

| |

|

| In popular perception Sita’s

agni pariksha is not put in the same category as the mandatory

virginity test Diana had to go through in order to prove

herself a suitable bride for Prince Charles, but rather

as an act of supreme defiance on her part. |

|

Sita of Folk Songs

INTERESTINGLY, the sentiments expressed in the interviews

I gathered are very similar to those expressed in a folk

song from Avadh, UP. In this woman’s song, Sita,

though hemmed in on all sides and betrayed even by Lakshman,

who leaves her in the forest on false pretenses, rejects

Ram even more strongly than some modern educated women

do. The story as unfolded here shows Ram ordering a reluctant

Lakshman to banish Sita out of the kingdom. This is the

one issue on which Lakshman, Ram’s devoted brother,

differs strongly and expresses his disapproval of Ram’s

resolve to send Sita away, but still has to reluctantly

obey the King Ram. On the way, Sita is thirsty and asks

for some water. Lakshman leaves her sitting under a sandalwood

tree saying he will be back soon with some water for her,

but never returns. She is heartbroken at this treachery.

In the forest when she is crying helplessly, ascetic maidens

provide her support and care. After the birth of her twin

sons, she sends the customary gifts through the barber

for Raja Dashrath, her mother-in-law Kaushalya and brother

Lakshman and tells the barber, “but do not go to

my husband.” When Ram learns through Lakshman that

his wife has given birth to sons, he is stunned with remorse

and grief. He sends Lakshman to fetch Sita. Sita refuses

point blank: “Go back to Ayodhya, brother in-law,

I will not go with you.” (Devra jahu lavti tu Ayodhya

ta hum nahi jabe). The sage Vashisth admonishes her saying:

“Sita, you who are so wise, renowned for your understanding,

have you taken leave of your senses that you have forgotten

Ram?” Sita

replies:

Guru, you who know what I went

through but ask me this question

As though you know nothing,

The Ram who put me in the fire, who threw me out of

the house

Guru, how shall I see his face?

Guru, I will do as you say,

I will walk with Lakshman a step or twain

But I will never in my life see the face of that heartless

Ram again

And may fate never cause us to meet again.

Some years later, Ram meets his sons by accident and questions

them:

Whose sons or nephews are you, Oh

children?

From whose womb did you take birth, Oh twin boys?

Luv and Kush reply:

We are the grandsons of Raja Janak and the

beloved sons of Sita.

We are the nephews of Lakshman -

And we know not the name of our father.

Thus Sita, in her rejection of Ram, goes to the extent

of giving her sons a matrilineal heritage — they

claim Janak and not Dashrath as their grandfather and

do not even own their own father. And when Ram comes repentantly

to take her back, this is how the folk song deals with

Sita’s reaction:

Sita Rani sat under a tree, and combed her

hair, combed her hair,

“Oh queen, leave now your heart’s anger

and come to live at Ayodhya,

Oh Sita, without you the world is dark and life utterly

fruitless.”

Sita looked at him one moment, her eyes filled with

anger,

Sita descended into the earth, she spoke not a word.

(Singh, 1986)4 |

| For a full translation of this folk song,

see Manushi No.8, 1981. |

Athavale is at pains to point out that Ram’s

abandonment of Sita was a symbol of the highest self

sacrifice. “Sita was dearer to Ram than his own

life. He had never doubted the chastity of Sita ...

For had it been so, he would not have kept by his side

the golden image of Sita during the sacrificial rites

[Ashwamedha Yagna].” (Athavale, 1976)5 |

| |

However, even a passionate devotee of Ram like Pandurang

Shastri finds it hard to give a totally clean chit to

Ram: “Once Ram appeared callous, even cruel.

Upon the death of Ravan,

after the |

|

battle of Lanka, Sita, extremely happy appears before Ram. Sternly,

Ram says to her, ‘I do not want you who has been looked at and

touched by another person. You may go wherever you want to. You may

go either to Bharat, Laxman, Shatrughan, or Vibhishan and stay with

any of them.’ We do not know for what purpose he was so harsh,

or what he intended to convey to Sita by these words, but it is equally

certain that they were terrible words ... Even the people who heard

Ram saying such bitter words wept. Everyone felt the bitterness of

those words, the injustice that was done, but none dared to protest

or plead.”6

The most powerful indictment,

however, comes from the people of Mithila, the region which is the

parental homeland of Sita. We are told that Sita’s being is

part of the very consciousness of Mithila; she is all pervasive

in the land, in the water, and in the air of Mithila. “Her

pain sits like a

heavy stone on the hearts of Mithila’s people.” (Khan,

1986)7 This sentiment comes through numerous folk songs

of the region. An account of what the injustice done to Sita means

to the people of Mithila is poignantly evident in several accounts

by leading Hindi writers published in the form of a joint travelogue.

This project was organised by the don of Hindi literature, Sachidanand

Vatsayayan, whereby a large group of Hindi writers travelled through

the region connected with Sita’s name starting from her birthplace

Sitamarhi on to Janakpur, Ayodhya and ending their journey in Chitrakoot.

The purpose of this project was to delve into the secret of why

and how the Ramayan, the story of Ram and Janaki, and the locales

associated with their names, have become part of people’s

consciousness and how it has influenced the value system of the

educated as well as the illiterate and defined their cultural identity.

(Singh, 1986)8

Sita is not just the daughter of Janak in this region but a daughter

of all Mithila because, as the folk songs of this region testify,

popular sentiment maintains that, had Raja Janak by chance not gone

to plough the fields that particular day, someone else from any

other jati might have gone and found her. In that case she would

have become that person’s daughter. Therefore, Sita is treated

as a daughter of every household in Mithila. In Mithila the entire

village is considered as naihar (parental home) not just one’s

actual father’s abode. (Khan, 1986)9 Therefore,

various folk songs show the entire people of Mithila grieving over

Sita’s fate.

In some folk songs women of different strata plead with their respective

husbands to go and fetch her back to her home after her desertion

by Ram. However, Sita in her pride and dignity refused to return

and brought up her two sons all on her own. Various writers of this

anthology describe how the dignity with which Sita suffered privations

after Ram’s painful rejection has remained alive in people’s

consciousness as if this injustice was undergone by their own daughter.

“Even today, people of Mithila avoid marrying off their daughters

in Marg-Shish because that is the month Sita got married. Even today,

people of Mithila do not want to marry their daughters into families

living in Avadh, in fact anywhere west of Mithila.

They repeatedly recite Sita’s

name in marriage songs but Ram’s name is omitted. At

the end of the song there is usually one line which says “‘such

like Sita was married into Raghukul [the family name of Ram]’”

(Dalmia, 1986)10. There is a beautiful folk song

of Mithila quoted by Usha Kiran Khan in which a daughter tells

her father what kind of a groom he should find for her. After

describing various qualities she is looking for, the daughter

advises her father: “Go search in the north, go south,

or get me a groom from the east. But don’t go westward,

O father, get me a groom from the north.” (Khan, 1986)11

This daughter of Mithila has a status higher than that of

Ram in her own region. In various polemical songs, Ram is

shown as inferior to Sita. (ibid)12 At the time

of marriage Shiv Parvati songs are more popular than Sita

songs. In this context it is well worth remembering that Ram

had to prove himself worthy of Sita before her father offered

his daughter to him. This is how one of the folk songs of

this region describes it: “Everyday Sita used to clean

and smear cowdung in the temple courtyard. One day her father

Janak saw her lift the heavy Shiv dhanush (bow) with her left

hand while smearing with her right hand the floor where the

dhanush was kept. At that very moment he vowed that he would

marry his daughter only to such a man who had the valour to

break that dhanush into nine pieces. Hence, the condition

of the swayamvar that Sita would only be given in marriage

to a man who could demonstrate

such exceptional |

|

strength.”13 People of Mithila still believe that

though Ram passed the initial test for winning her, he failed to prove

a worthy husband. Another writer, Shankar Dayal Singh, commented on

how he sensed the all pervasive sentiment of anguish and pain in the

collective consciousness of the people of this region at the injustice

done to Sita. He goes on to say:

“This region has taken

a strange revenge in a silent way. From pauranic times, everywhere,

in every village and small town (kasba) are found Shri Janaki mandirs

where Ram and Lakshman are also present along with Janaki. But the

temples are named after Sita as evidence that somewhere the pain

of Sita is still hurting the folk sentiment consciousness as though

saying: ‘Ram, you made our Sita walk barefoot in the forests.

Ravan challenged your manhood and forcibly abducted Sita. Though

this mother of the universe (Jagajannani) went through the fire

ordeal to prove her

innocence, you abandoned her. Our daughter, our sister was treated

thus by Ayodhya. But we are careful of our maryada (honour). That

is why O Ram, we will keep your idol in the temple. We will even

worship it, but the temple will be known in Sita’s name.’

That is why the whole area is littered with Shri Janaki mandirs.

There are Sita legends attached to every spot, even trees and ponds.”

(Singh, 1986)14

Vatsayan comments on how in Chitrakoot people offered them leaves

from a tree believed to be the ones which the abandoned Sita used

to eat in order to still her hunger. What is the proof offered?

The leaves tasted sour and if you drink water after chewing some,

the water tasted sweet. So the lore has it that Sita mai used to

drink water after filling her stomach with these leaves and that

sweet aftertaste helped sustain her through days of destitution.

Thus, her memory is kept alive in every aspect of the natural as

well as the cultural landscape of Mithila. As writer Lakshmi Kant

Varma sums it up: “Sita sahanshilta (quality of dignified

tolerance) is written on every leaf of Balmiki Nagar” —

the ashram where she spent her years of banishment. (Varma, 1986)15

|

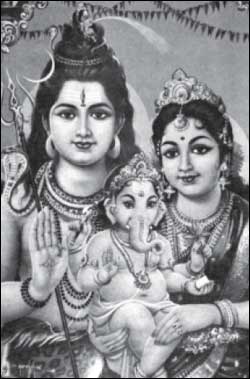

| A modern calendar representation of Shiv and Parvati |

|

The Television Ram

Even in the rest of India, very few people endorse Ram’s

behaviour towards Sita. He has not been forgiven this injustice

through all these centuries, despite his being a revered figure

in most other ways. In this context, I am reminded of the

time when Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan was being telecast

over Doordarshan. As the story began approaching the point

when Sita was supposed to undergo her agnipariksha the serial

makers were flooded in advance with so many letters of protest

against the depiction of Sita going through the fire ordeal

that Sagar was forced to deviate from his text and show the

agnipariksha to be a mock one. The TV Ram was made to clarify

that he did not doubt Sita’s chastity. Clearly, Ram’s

injustice to Sita has hung so heavily on the collective conscience

of Indians that they are willing to demand that a sacred text

be altered. In this new text, determined by contemporary devotees,

maryada purushottam Ram was being ordered to behave better.

Disqualified Husband

The final rejection of Ram by Sita has come to acquire a

much larger meaning in popular imagination than one woman’s

individual protest against the injustice done to her. It is

a whole culture’s rejection of Ram as a husband. For

instance, people will say approvingly: “He is a Ram-like

son, a Ram-like brother, or a Ramlike king.” But they

will never say as a mark of approval, “He is a Ram-like

husband.” If Ram had not been smart enough to win Sita

for a wife by his skill in stringing Shiv’s bow, if

instead Janak had decided to match their horoscope and it

had predicted that Sita would be abandoned by him, I doubt

that Ram would have ever found a wife. No father would have

consented to give his daughter to a man like Ram — his

claims to godlike perfection notwithstanding. Most people

I talked to echoed this sentiment: “Ram honge bade admi

par Sita ne kya sukh paya?” (Ram may have been a great

man, but what good did it do Sita?) |

Thus, not just modern day Sitas but even traditional women

and men reject Ram as an appropriate husband. Indian women’s

favourite husband has forever been Bhole Shiv Shankar — the

innocent, the trusting, the all devoted spouse who allowed his wife

to guide his life and his decisions. Unmarried women keep fasts

on Monday, the day assigned for Lord Shiv and pray that they may

be blessed with Parvati’s good fortune. Shiv and Parvati are

the most celebrated and happy couple in Hindu mythology, representing

perfect joy in togetherness, including in their sexual union. Their

mutual devotion, companionship and respect for each other are legendary.

Shiv is not seen as a bossy husband demanding unconditional obedience

but as one who respected his wife’s wishes, even her trivial

whims. To quote Devyani (a middle aged woman working as a domestic

help in my neighbourhood): “Bhole Shankar never caused pain

to his wife. He would indulge every whim of hers. Only when a man

behaves with such respect for his wife can you have a sukhi grahsthi

(happy domestic life).”

It is significant that pauranic descriptions of Shiv show him as

the least domesticated and the most rebellious of all the gods,

one whose appearance and adventures border on the weird. He is so

unlike a normal husband that Sati’s father never forgives

her for marrying Shiv. Yet Hindu women have selectively domesticated

him for their purpose, emphasising his devotion to Sati/Parvati

as well as the fact that he allowed his spouse an important role

in influencing his decisions. At the same time these women conveniently

overlook the many very prominent and contradictory aspects of his

life and deeds.

Interestingly, Parvati is not

just seen as a grihalakshmi, as someone whose reign is confined

to the domestic sphere. She often also controls and guides

Shiv’s dealings with the outside world, constantly goading

him to be more generous, compassionate and sensitive to the

needs of his bhakts.

While there has been a lot of discussion and analysis of

the demands put on women in the Hindu tradition, the sacrifices

expected of ideal wives, we have failed to evaluate the demands

put on an ideal husband. The Hindu tradition might valourise

wives who put up with tyrannical husbands gracefully but it

does not valourise unreasonable husbands. On the contrary,

it places heavy demands on them and expects very high levels

of sexual and emotional loyalty from them if they are to qualify

as “good husbands”. Shiv, for instance, is perceived

as someone who cannot live without Parvati. He is said to

have no desire for other women. He is supposed to have roamed

around the world like a crazed being carrying Parvati’s

dead body on his shoulders after she jumped into the fire

to protest against her father’s insult to her husband.

His tandava threatens to destroy the whole world and he rests

only after he has brought her back to life. However, most

women realise that a Shiv like husband is not easy to get.

Therefore, they need other strategies to make husbands act

responsibly.

There are several practical reasons why Sita-like behaviour

makes sense to Indian women. The outcome of marriage in India

depends not just on the attitude of a husband but as much

on the kind of relationship a women has with her marital family

and extended kinship group. If, like Sita, she commands respect

and affection from the latter, she can frequently count on

them to intervene on her behalf and keep her husband from

straying, from behaving unreasonably. Similarly, once her

children grow up, they can often play an effective role in

protecting her from being needlessly bullied by her husband,

and bring about a real change in the power equation in the

family, because in India, children, especially sons, frequently

continue living with their parents even after they are grown

up. A woman can hope to get her marital relatives and her

children to act in her favour only if she is seen as being

more or less above reproach.

Most women realise that it is not easy to tie men down to

domestic responsibility. You need a lot of social and familial

controls on men in order to prevent them from extra-marital

affairs which can seriously jeopardise the stability of a

marriage. Thus, they think it is best to avoid taking on the

ways of men. To respond to a husband’s unreasonableness

or extramarital affair by seeking a divorce or having an affair

herself would only allow men further excuses

to legitimise their irresponsible

behaviour. Thus, it is a |

|

| Uma-Mahesvara, Khiching Museum |

| |

|

| The Hindu tradition might valourise

wives who put up with tyrannical husbands gracefully

but it does not valourise unreasonable husbands |

|

strategy to domesticate men, to minimise the risk of marriage break-down

and of having to be a single parent, with its consequent effect on

children. A man breaking off with a Sitalike wife is likely to invite

widespread disapproval in his social circle and is therefore, more

likely to be kept under a measure of restraint, even if he has a tendency

to stray.

|

| I am grateful to my friend Berny and

my colleague Dhirubhai Sheth for their helpful comments

and suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper. |

|

While for women Sita represents an example

of an ideal wife, for men she is Sita mata (jagjannani), not

just the daughter of earth but Mother Earth herself who inspires

awe and reverence. By shaping themselves in the Sita mould,

women often manage to acquire enormous clout and power over

their husbands and family.

References:

1. |

Sudhir Kakkar, 1978, quoting from P. Pratap’s

unpublished thesis in The Inner World, Oxford University

Press. |

2. |

Vidya Bindu Singh, 1986. ‘Sita Surujva ke Joti’,

in Sacchidananda Vatsayan (ed.) Jan, Janak, Janaki, pp.

125-26(New Delhi, Vatsal Foundation). |

3. |

Kalidasa. Raghuvamsha. 14. 61 |

4. |

Vidya Bindu Singh, 1986. ‘Sita Surujva ke Joti’,

in Sacchidananda Vatsayan (ed.) Jan, Janak, Janaki, pp.

122-26(New Delhi, Vatsal Foundation). |

5. |

Shastri Pandurang V. Athavale, 1976. Balmiki Ramayana

- A Study, pp. 161- 2 Bombay, Satvichar Darshan Trust. |

6. |

ibid |

7. |

Usha Kiran Khan, 1986. ‘Sita Janam Biroge Gel’,

in Sacchidananda Vatsayan (ed.) Jan, Janak, Janaki, op.cit,

pp.119. |

8. |

Karan Singh, 1986. Introduction in Sacchidananda Vatsayan

(ed.) Jan, Janak, Janaki, op.cit. |

9. |

Usha Kiran Khan, 1986, op.cit, pp. 120. |

10. |

Ila Dalmia, 1986. ‘Sita Samaropti Vaam Bhagam’,

in Sacchidananda Vatsayan (ed.) Jan, Janak, Janaki, op.cit,

p. 32. |

11. |

Usha Kiran Khan, op.cit, p. 120. |

12. |

ibid p.121 |

13. |

Vidya Bindu Singh, op.cit. p. 122. |

14. |

Shankar Dayal Singh, 1986.‘Ek Gudgudi, Ek Vyathageet’,

in Sacchidananda Vatsayan (ed) Jan, Janak, Janaki, op.cit.

p.53 |

15. |

Lakshmi Kant Varma, 1986. ‘Kabir Ki Do Samadhiyon

Ke Beech’, in Sacchidanada Vatsayan (ed) Jan, Janak,

Janaki, op.cit. p.73. |

|

|